A complete series of cultural memories came to mind: the Egyptian màstabas, the Etruscan tombs, the Aztec structures… As if this piece of artillery fortification could be identified as a funeral ceremony, as if the Todt Organization could manage only the organization of a religious space. […] This was nothing but a broad outline, but from then on, my curiosity would be quickened and I could guess that these littoral boundary stones were to teach me much about the era, and much about myself. […]

Paul Virilio while visiting the Atlantic Wall on the northern-France coast in 1958.

Treachery over the Maginot Line

Larry Wilson was a warplane pilot, lieutenant of the 89th Escadrille de Reconnaissance, fighting against the Nazi invasion on the French border in World War II. Accused of treachery and dismissed in dishonor by the will of Captain James Hammer, he engaged in a dangerous mission of espionage to redeem himself. Falsely accused, Wilson wanted to prove his worth to Major Massoine and to his fiancé Jean, who had been previously bothered by Captain Hammer, and get back his role in the Allied army. By the end, thanks to Wilson braveness, it surprisingly turned out that Captain Hammer himself was a spy for the Nazis; Wilson killed him in a breathtaking air battle and, due to his acts of heroism, was later named Chevalier of the Legion of Honor. This is just one of several other novels narrated in the first issue of the American magazine Air Adventure published on December 1939: stories of brave Allied soldiers from the front, between explicit and violent propaganda – “All Nazis must Die!” we read in capital letters in the first pages –and entertaining tales of bravery, dramas, rivalry and romance. In these pages, we guess the role of fictional narrations at the side of the ones that were almost to constitute the raw materials for historians. After all, the difference between a novelist and a historian, points out Paul Ricoeur, is just about the promise of the author and the expectation of the reader about truth (Ricoeur, 2000). However, those tales were something more than pure fiction: firstly, they were based on real facts and they were fundamental to grow a national pride as a cultural union. Their authors were building a proper mythology: a mythographist indeed can be described as someone who has both the authority of a historian as well as the poetry of the novelist. Nonetheless, without going too far, we might just consider that between history and stories, the latter assume the fundamental role of personalising historical facts which otherwise would result macroscopic, non-tangible or even abstract. It is something which is able to move the will of a nation talking to people about other people, gaining political approval throughout empathy. Michael Wade, the author of the novel, had been particularly able to give a specific face to the act of rejection of the Nazi’s threat and, at the same time, to focus on a specific and emblematic place: a place which would have become mythological itself in representing the whole conflict. A crucial part of Larry Wilson adventure takes part when he and his comrade Ledeau, returning from the espionage mission, cross the Maginot Line which marked the border between Germany and France. Flying over it, from the enemy to the friendly front, meant salvation: a single but hulking line collected meanings of alliance, invasion, defense, threat, life, death, hopes of victory and fears of defeat.

Promise and Failure

The Maginot Line was a line of concrete fortifications, obstacles, and weapon installations built, between 1930 and 1936, along the Franco-German border by the French government thanks to the member of the Chamber of Deputies, veteran of World War I, André Maginot. Persuaded that the Treaty of Versailles did not provide France with sufficient security, Maginot pushed for more funds to repel the attack safeguarding vital industries in the Alsace and Lorraine regions. To tell the truth, he became the chief advocate for the Line also for personal reasons: the barrier, in fact, was a sort of revenge act to the invasion that destroyed his home in Revigny-sur-Ornain. This happened during World War I, in which he served the French army as sergeant along the Lorraine front, remaining deeply wounded. The Maginot Line was more than 16 miles deep and was made up of a series of separate defensive layers. Up front were camouflaged observation points positioned right along the German border, to the rear were anti-tank, mortar and machine gun emplacements, underground infantry bunkers or casemates. There were 142 artillery forts, 352 casemates and 5,000 smaller fortifications overall, many of which were laid out across the landscape to create interlocking fields of fire. Supporting the Line was a network of mobile rail guns that could bring extra fire to bear where needed. Overseeing the entire chain was a string of 78 of hilltop fire control decks that enabled observers to direct artillery barrages onto enemy troop and vehicle concentrations at will. Installations were also linked by a labyrinth of tunnels, the whole system had its own self-contained telephone and wireless communications infrastructure. The sprawling underground casemates were home to barracks, mess halls, hospitals and even recreation areas. Each ouvrage had its own power generator, hot and cold running water and was stocked with enough supplies to withstand a lengthy siege. Yet despite all the amenities, dwelling on this border was not always pleasant: the passageways were humid and cold and the sewage system was prone to backups. Strategically, the Line had two main purposes. It would stop an invasion long enough for the French to fully mobilize their own army, and then act as a solid base from which to repel new incursions. The Maginot Line was not a single continuous structure but was composed of over five hundred separate buildings. The key units were the large fortresses located within 9 miles of each other: these vast bases held over 1,000 troops and housed artillery. Other smaller ouvrages were positioned between the larger strongholds, holding either 500 or 200 men. From this description a dense, multi-layered border system emerges: a “continuous line of fire” designed with the latest in technological and engineering know-how. As Paul Virilio affirmed, the construction of this war landscape in the first half of the twentieth century was connected with a revolution of the speed of vehicles, weapons and even projectiles that in fact lead to the production of strategic and accelerated infrastructures that he called an “an archaeology of the brutal encounter.”(Virilio, 1994). With the outbreak of World War II, the Nazi planned to invade France. On May 10, 1940, the German’s northern army attacked the Netherlands with the so-called Fall Gelb Operation, moving into the neutral Belgium. Such an unexpected move would no doubt draw other European powers, namely Great Britain, into a conflict and provoke world opinion against Berlin. The advance continued unabated for some days; by June, German forces had swung down behind the Maginot Line, cutting it off from the rest of France. From the time when World War I had left France desperate to guarantee the safety of its borders, the Maginot Line became a symbol of national pride and invincibility. Its ouvrages were futuristic subterranean dwellings, such a marvel that even the Maginot Line propaganda made a great impression not only in France stimulating other nations in those years to construct lines of resistance. Beginning in 1936, Greece started the construction of a 100-mile long line along its frontier with Bulgaria. Similarly, Czechoslovakia assembled its own network of bunkers, pillboxes and artillery forts on its border with Nazi Germany as early as 1935. Even the Third Reich constructed fortifications opposite the Maginot Line in the two years leading up to the outbreak of the war. After World War II, though, the Maginot Line was portrayed in many different ways. Predictably, the Line received severe criticism becoming an object of international derision since it appeared as an obvious target and its sole purpose had been to stop another invasion. It was acknowledged as “[…] a foolish misdirection of energy, a dangerous distraction of time and money and a pitiful irrelevance […]” (Ousby, 1999). Opposing arguments, though, claim that the Line itself was wholly successful: it was either another part of the plan –for instance, fighting in Belgium –or its execution that failed. Discussions on the Maginot Line, then, had other ramifications. The Line fortified a defensive attitude that slowed the development of new weapons and tactics: this “Maginot mentality” spread across France boosting a non-progressive thinking in government. Ultimately, the “Maginot Line concept” has been taken as a universal metaphor to indicate something that is thought to be effective and that, on the contrary, completely fails.

A Unique Piece of Architecture

Despite it had any decisive role in the conflict – even if one may rightly object that the fact it obliged the Nazis to get through Belgium was anyway crucial – the Maginot Line is often mentioned as one of the greatest “war architecture” of all times. Nonetheless, isn’t it fundamentally an oxymoron to talk about war architecture, or at least does such a definition implies an overly superficial and inclusive use of the term “architecture”? It is fairly immediate to believe that something – as a fortification or a bunker – which is built solely according to technical and performative issues and, most of all, without any kind of aesthetic intentionality, could hardly be defined “architecture”. On the other hand, though, it would be also reductive – to the point of being iniquitous – to judge those war buildings without the awareness of the cultural role in terms of memory we attribute to them in present times. Talking about memory – or better about “sites of memory”– Pierre Nora clarified a pivotal definition: “A lieu de mémoire is any significant entity, whether material or non-material in nature, which by dint of human will or the work of time has become a symbolic element of the memorial heritage of any community” (Nora, 1996). A site of memory, hence, is where something took place: the act of taking place, unlike the naiver happening, means the constitution of precise indicators for historical knowledge. To take advantages from Nora’s idea we need to state that, not by chance, a border is actually a place. On the territory of the border – be it political, cultural or military – in fact is possible to identify a space in itself, or better a place, with its inhabitants that somehow use it and change it constantly. The border is that intermediate and third place – with respect to what it simultaneously divides and connects – in which juxtapositions and antinomies manifest themselves completely. Piero Zanini looks at them as places with their own thickness and measure, with their characters derived from the set of relationships that converge and are reflected on them (Zanini, 2000). According to him, testing the border and experiencing the liminal condition that it inevitably generates, means getting in touch with its contradictions and its boundless vivacity. This involves the basic conceptual leap of considering not just the border space, but the border as a space. By applying the hermeneutical category of place to the border, we could reconsider the first question: are we really talking about architecture referring to the Maginot Line? And, in particular, are architectures sites in which we can observe acts of taking place? It is again Paul Ricoeur that, extending the concept of “site of memory,” gave a cue establishing the essential duality of “document/monument” where each word enriches the meaning of the other. Documents and monuments tell stories that constitute the raw material for the building of a history; through this process, moreover, they become posthumous representation of a fact. By representing a fact, we invest objects with meanings letting them become symbols: that is the place we find architecture, exactly in that act of representation which attributes significance to the bare matter. Without any doubts and in light of the importance assumed even after its disposal, the Maginot Line is an emblematic place able to represents stories of and from the border. Independently from its practical use, in fact, even this 400-km long line of concrete fortifications built as a physical manifestation of French fears can be acknowledged both as a “monument” and a “document”. In this perspective and due to its representative role, the Line suddenly finds itself to be a unique – even if a posteriori –piece of architecture.

Note to the text

The entire research, the choice of the theme and the development of the topic was curated by both authors equally. More specifically the survey was written by Francesco Bacci (from «Larry Wilson was a warplane pilot…» to «…an archaeology of the brutal encounter») and Beatrice Moretti (from «With the outbreak of World War II…» to «…even if a posteriori– piece of architecture).

Reference List

- Nora, Pierre. 1996. “Preface to English Language Edition: From Lieux de memoire to Realms of Memory”. In Realms of Memory: Rethinking the French Past, Columbia University Press.

- Ousby, Ian. 1999. Occupation: The Ordeal of France, 1940-44, 14. Paperback, England.

- Ricoeur, Paul. 2000. La mémoire, l’histoire, l’oubli. Paris: Sauil. Ed It. 2003. La memoria, la storia, l’oblio. Milano: Raffaello Cortina Editore.

- Virilio, Paul. 1994. Bunker Archeology. Cambridge: Princeton Architectural Press.

- Zanini, Piero. 2000. Significati del confine. I limiti naturali, storici, mentali, Milano: Bruno Mondadori Editore.

Photo Credits

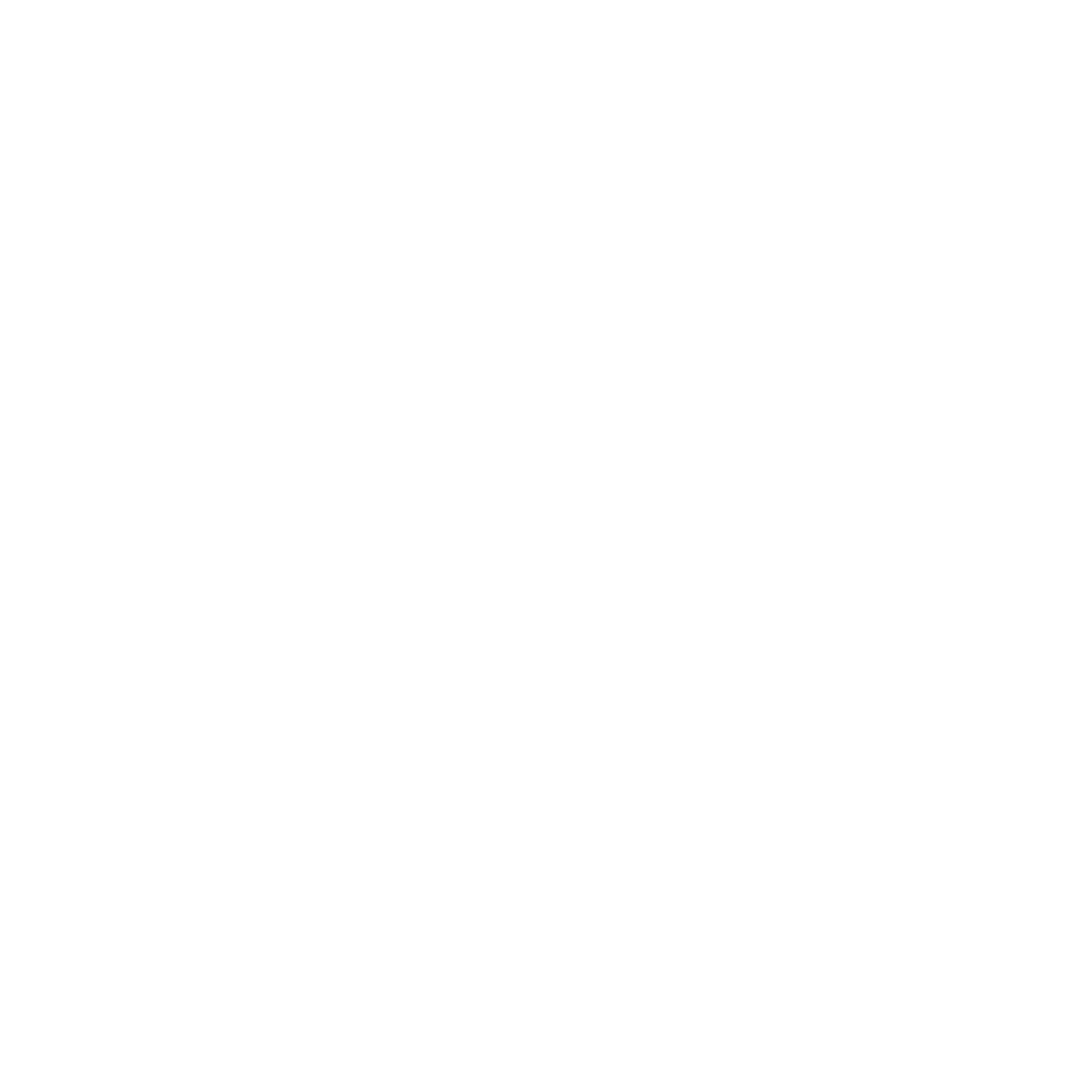

- Photo: Key cities of Rhineland within reach of allied armies

Author : Los Angeles Times, Owens, Charles H.

Date: 1944

Publisher: Los Angeles Times

Source: David Rumsey - Photo: American soldiers standing at battery 8 location that is one of the 75 mm gun batteries of the Hackenberg fortications of the Maginot Line near Metz, France. This battery was used by the Germans to shell the advancing American 3rd Army of General Patton.

Date: 1944

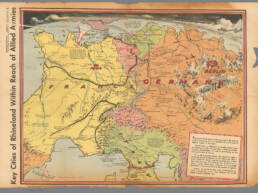

Source: Maginot Line Public Domain, Wikimedia Commons, National Archives and Records Administration, cataloged under the National Archives Identifier (NAID) - Photo: Maginot line cloche on the Mont Gros

Author: Elianhen

Date of creation: 2015

Source: Maginot Line Public Domain, Wikimedia Commons - Photo: Electric stove equipping kitchens for large works, photo taken in Rochonvillers during a peace exercise

Author: Les Bergers des Pierres – Moselle Association

Date of creation: 2018

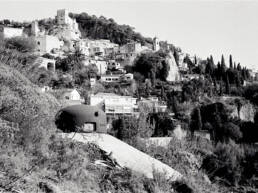

Source: Maginot Line Public Domain, Wikimedia Commons - Photo: Cover of Lieutenant-Colonel René Rodolphe, Battles in the Maginot Line, Editions M. Ponsot, Paris

Date: 1949

Source: BMIAA

Francesco Bacci

PhD Architect whose research concentrates on the relations between mythology and architecture. He published essays on architectural myths and edited a book entitled “Dear Prudence”(2019).

On Instagram: @frncscbcc

Beatrice Moretti

PhD Architect, her research concerns port cities. She is author of the book “Un colle, un transatlantico, un nome. Tre storie sul porto di Genova”(2018).

On Instagram: @beatricemoretti__